DENVER — During Black History Month, Carlotta Walls LaNier — the youngest member of the Little Rock Nine who braved mobs, threats, and violence to integrate Central High School in 1957 — is usually in demand as a speaker.

But this year, and last, were different.

“Well, I have been denied, even though there were contracts out to speak at various places,” LaNier said. “With the executive orders against DEI programs, against civics and historical sites, and the historical education that everyone should really have, my speaking engagements just started drying up. And it's not just mine, I've talked to others throughout the country, and it's the same thing that has happened to them."

But in her Colorado living room, on a January Tuesday morning, LaNier shares her story for those who want to listen.

Growing up in Little Rock, Arkansas

In 1957, Carlotta Walls, as she was known then, was 14 years old, growing up in Little Rock, Arkansas.

She wanted to be a doctor and dreamed of going to Little Rock Central High School, which was closer to her home but all-white. Segregation was the law of the land, and Black and white children were forbidden from attending the same schools.

“I knew it had more than what we had. Everything that was at the Black Junior Senior High School was a hand-me-down. So, with Central being one of the top 40 high schools in the nation, I mean, who wouldn't want to go there?” LaNier said.

In 1954, the Brown vs the Board of Education decision legally ended segregation in schools. So when LaNier had the opportunity to sign up to be one of the first Black students to attend Little Rock Central, she did.

But that decision came with many sacrifices.

The Little Rock Nine

One hundred and eighteen Black students signed up to attend Little Rock Central, and 39 were selected to meet with the superintendent, who outlined the rules for attendance.

“You could not be a part of the student council; you could not be working on the newspaper or the yearbook; you could not be in sports,” LaNier said. “Well, I knew I was not going to continue to be captain of my basketball team or the cheerleading team … I just figured, well, maybe it'll change.”

LaNier said that during the summer of 1957, she was notified that she had been selected to attend Little Rock Central High School.

“Actually, there were 10 of us on the first day, and then after all that took place that first day, I think her parents just told her, ‘No, you're not going back.’ But the nine of us were really how that term came about, through the media, they called us the Little Rock Nine,” LaNier said.

The first day of school

On the first day of school, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus deployed the National Guard to block the Little Rock Nine from entering the building.

“We were turned around and had to leave. And then that is when the Arkansas NAACP leader, who was Daisy Bates, got in touch with the Legal Defense Fund in New York and let them know what was happening. And fortunately, Thurgood Marshall, who was the man at the Legal Defense Fund, came down along with the attorney Wiley Branton, who represented us in the federal courts. So that went on for the next two and a half weeks,” LaNier said.

The courts forced the governor to let the students attend the school.

“So once we did get in, September 23rd was probably the worst day when the mob had grown to over 1,000 people out there, and reporters were being beaten Black and white,” LaNier said. “January 6th reminded me of September 23rd. I just think of about the 1,300 people out there trying to rush to school or wanting the kids to get out of the school. Kids were jumping out of windows because their parents were telling them to come out. They would yell, ‘The n—-ers are coming,’ you know, this sort of thing. So, it was a very hard day,” she said.

LaNier said that eventually, a police officer came to her classroom.

“My teacher told me to gather my things and follow this man, which I did. And we all were brought to the office, the principal's office. We were told to follow the policemen, and they were getting us out of the school because the crowd wanted to hang someone," she remembers. "That is what the crowd was saying, you know, so it was an awful day. We were brought down into the bowels of the school and put into two police cars. And then I heard the one policeman tell the other policeman, ‘Put your foot to the floor and don't stop for anything.'

“I think about that day, even today, and the rush of that car going as fast as it was going and up this ramp, and all of a sudden the doors open, and anyone going across that sidewalk would have been killed as fast as we were going,” she added.

The next day, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to restore order. Soldiers stood outside all nine students’ classrooms and escorted them to class.

But not even soldiers could stop the constant harassment from other students.

“Being spat upon, being kicked, being pushed down the steps, lockers being broken into every day, to the point that if you ever see those pictures, we are carrying a lot of our books and our work,” LaNier said.

The second year

The next school year, the governor shut down all public high schools in Little Rock. LaNier took correspondence courses and moved in with an aunt in Chicago to attend school there. But after a year of public and court pressure, they were reopened in 1959.

“Jefferson Thomas and I were the only two of the remaining Little Rock Nine to go back to Central, and there were three other Black kids,” LaNier said.

LanNier said 1959 was better.

“I give credit to the senior class president and his group for trying to maintain some semblance of going to school. They didn't want all of what had taken place in ‘57-’58 to continue, and they were trying to corral those that were giving us trouble,” LaNier said. “We didn't have the guards there. We were on our own as far as that goes. Still had some problems, but overall, we all dealt with them the best way we could.”

But the uncomfortable peace didn’t last.

Lanier’s home is bombed

“Unfortunately, in February of 1960, my home was bombed. I was told that, in fact, I was the first student throughout the United States to have their home bombed due to integrating a school. I was determined to go back,” LaNier said. “Fortunately, no one was injured, and it was my mother, my sisters and I who were there. My father was working at his father's place.”

LaNier said that about two weeks after the bombing, authorities made three arrests.

“They picked up my father and my friend up the street, Herbert Monts and a friend of my father's, and brought them in. The FBI picked them up and held my father for 72 hours, trying to beat a confession out of him, which he did not confess to. But unfortunately, Herbert was 16, just like me. He and I were born on the same day, and knew each other from early on. He was beaten, and he signed the papers that he had planted the bomb, which he hadn't. And he spent two and a half years and a five-year sentence for bombing my home, which I know he did not,” LaNier said. “It didn't make sense. But anyway, that was a railroading that went on then, and unfortunately, that same sort of process is going on today.”

No one else was arrested for the crime. But even after all of that, LaNier finished what she set out to do.

Life after Little Rock Central High School

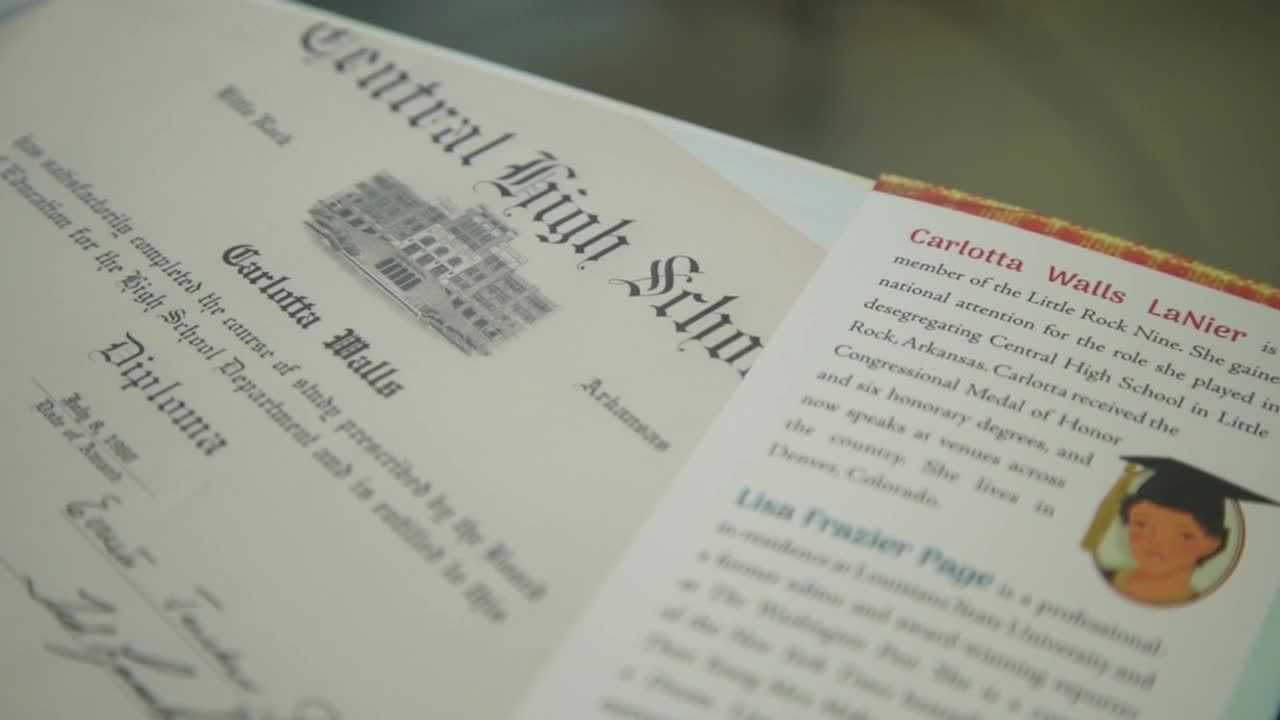

“I received my diploma on May 30th of 1960, and there was a little party that Jefferson's parents and my parents put together that we had that night, and that next morning, I took the first thing smoking out of Little Rock,” she said. “I went off to Michigan State. My uncle did not want his children to go through what I was going through. They're younger, and they moved out here and in, I think it was in ‘59, moved here to Denver.”

LaNier visited her uncle, aunt, and cousins in Denver between her first and second years of college.

“I was getting letters at Michigan State saying you should come and visit, because I can play golf 360 days out here, and the sun shines all the time,” LaNier said. “I just decided that I was going to move here, and I left a scholarship at Michigan State, came to Denver, and lived with them in Park Hill.”

LaNier graduated from the University of Northern Colorado and spent decades building a career, family, and life in the Centennial State. She’s received worldwide recognition for her civil rights work and was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999 by President Bill Clinton.

But these days, she’s faced pushback for sharing her story.

“I'm not here to denigrate people today for what took place, you know, 100 years ago or 200 years ago, or what their parents did. I'm asking you to break the chain. That's all I'm asking. If you don't believe in what took place, then stand up for what is right now,” LaNier said.